Origins of Astronomy

- M. Josh Roberts

- Dec 9, 2025

- 11 min read

Thank you for joining me at the Monterey Peninsula College campus, a place I've visited before in my youth, and I'm honored to be invited by the Monterey Institute for Research in Astronomy. MIRA was the first folks to give me the chance to operate a telescope by myself, and all these years later, I blame them for the trajectory my life has taken - Astronomy has become and remained a lifelong passion of mine and I am doing everything I can to share that trajectory with others.

The story I want to share is one that many of you have likely heard fragments of, as it chronicles the evolution of a science dear to my heart and, I suspect, to yours: astronomy. Astronomy is a vast science, spanning the globe and countless generations. Today, I want to focus on what I call "the astronomy of place." Modern astronomy often occurs in massive observatories, space telescopes, supercomputing sites, or academic "ivory towers" that aren't always accessible to everyone. The astronomy I'll discuss today, however, is more accessible to more of us, even if the true origin of astronomy is well and truly lost to time.

How old is astronomy? the best answer I can give you is OLD. Really old. Maybe as old as people, but the evidence we have dating back to prehistory is almost always in the forms of physical materials - artifacts and sites, and the oldest astronomical objects are potentially the Ishango bone (Found near the Semliki river in the DRC) which has scoring that may reflect a lunar calendar and is thought to date back to a whopping 20 thousand years before the present.

A close second would be Aurignacian bone, which may depict both moon phases and a sequence of successive observations, making it arguably a better astronomical log than some students turn in today.

To illustrate the astronomy of place, I'll start with something familiar to many, especially those who, like me, grew up in the Salinas Valley. However, the story I'm about to tell is not the astronomy of the Salinas Valley – that's not my story to tell. For information about the astronomy of the indigenous people of this land, you should seek out the Rumsen Ohlone. Their knowledge holders and ensure they are compensated. My story, instead, is about the development of astronomy in Central and Western Europe, seen through the lens of the "Únětice people," a tradition I am more distantly connected to, as it is no longer a living practice. Given its ancient past, even those currently living in Central to Western Europe are likely as distantly related to these people as I am.

How is this connected to the astronomy of the Salinas Valley? Like the Únětice people, I began my life in a fertile river valley where much farming took place. In such a location, if you look towards the rising sun, you’ll notice nearby geographical features – distinctive hills or trees – marking its position on the horizon.

If you observed a few days or weeks later, you'd notice the sun's position relative to the horizon had shifted.

At this time of year, you would almost certainly notice the sun moving its rising position southward each day, rising a little further south than the day before.

This continues until the sun seems to pause, then begins moving in the opposite direction, slowly marching northward day after day, sunrise after sunrise. You would observe a similar progression for the setting sun, moving southward and eventually northward.

Months later, about six months into the year, you would notice the sun pausing its northern progression and beginning its return trip south. As a farmer in a valley, you would know that parts of the year get colder and warmer. Day after day, you would expect things to be generally warming up or cooling down. By noting the daily temperature, you could instantly divide the year into four segments: cold and warming, warm and warming, warm and cooling, and cold and cooling. Today, we call these winter, spring, summer, and fall. Coincidentally, and entirely related, the sun's motion on the horizon aligns with these points. Its northern progress could be seen as warming, and its southern progress as cooling. When the sun rises north of due east, it is warm; when it rises south of due east, it is cold. This provides a perfect understanding of how seasons relate to our position on Earth. All you need to do is carefully mark where the sun rises on these four dates, with two of them sharing the same position - the equinoxes.

But then, imagine being politely but firmly told to leave your fertile river valley by some less-than-friendly neighbors. In a new location, perhaps a broad, flat plain, your previous landmarks are no longer visible or accurate. To adapt, you could stand at your front door or a special spot and observe where the sun rises on the solstice – the day it changes direction. You could mark the summer solstice with some physical object, maybe a log or a rock. Now you have the sun's farthest northern point, allowing you to predict and remember the farthest north rising position and that evening, you can mark the setting position. You've started rebuilding your information. Now, you just wait six months and mark the sun's southernmost rising position for the winter solstice – perhaps with wood if you're practical, or stone if you're feeling ambitious. By also marking the rising and setting points of the equinoxes, you've essentially recreated your data set from your valley home in your new plain home.

This system is great for tracking the sun's position. If you look at where you've placed your markers, they form a circle. If you decided to make this more elaborate and opulent, decorating it with pizzazz and hanging elements, you would have created a wonderful wood henge – or a Stonehenge, if you're feeling ambitious. That's exactly what a henge is: it allows us, from a specific position, to observe where the sun rises and sets. This is an observatory by any measure, created by someone intimately connected to seasonal patterns and the sun's position, which dictates those seasons. Understanding the sun's position provides valuable information about current and future weather.

But what happens when those "jerks" from the next valley want to take over your cool henge? Perhaps you bury it, burn it, or simply flee. If you're going to rebuild, you'll want to do so in a way that prevents its loss. The story I've told so far could be attributed to the Corded Ware and Beaker cultures – farmers who were displaced from their valleys. They became the "Únětice people" in regions of central Germany, where they found broad, open, flat areas and very hilly regions. They were also mastering metallurgy, and with this incredible new science, they created something amazing and special: not a henge, but a disc.

This disc, the so-called Nebra Sky Disc, encodes much of the same information. It is, in essence, a portable henge.

The Nebra Sky Disc, an almost 4,000-year-old bronze disc dating back to around 1800 BC, is often considered the oldest scientific depiction of the night sky known to humanity. Although it has undergone modifications, its depiction of celestial bodies is evident. Gold inlays on the disc highlight key features: a crescent, a disc, a star cluster, and two golden arcs (one of which is now missing but known to have existed).

While many background stars are depicted as gold speckles and seem to have been repositioned over time, the two golden arcs are particularly significant. They represent the arc of the rising sun and the setting sun, each tracking its progress from north to south. This feature allows for the calibration of a "henge" (an ancient monument), as measuring the angle between the northernmost and southernmost rising or setting points of the sun would instantly calibrate a structure at those latitudes. This makes the disc a practical astronomical tool.

The people who created the Nebra Sky Disc, the Únětice culture, were skilled in bronze and gold work. Their successors, the Hallstatt and La Tène cultures, produced even more exquisite gold objects, influencing much of what is now called Celtic art.

The star cluster in the center of the disc is identifiable as the Pleiades (M45). The disc also features a full and crescent moon. While some interpret these as a full moon and a solar disc, the sun is more accurately represented by the golden arcs and later, the solar boat symbol (a late addition). The two lunar depictions are significant because the moon in these phases, alongside the Pleiades, occurs twice a year.

The crescent moon near the Pleiades (in the constellation Taurus) signifies that the sun is also near the Pleiades, as the crescent moon is always close to the sun. This alignment, occurring in mid-April, would have indicated the ideal time for planting.

Conversely, the full moon in Taurus, approximately seven months later (around October 6th in the current year), would have marked the harvest season.

Thus, the Nebra Sky Disc provided a comprehensive seasonal calendar, indicating the summer and winter solstices, and planting and harvesting times. The holes around the disc's edge suggest it was likely hung, possibly in a tent, and used to aid in the construction of other astronomical alignments. This sophisticated level of prehistoric astronomy challenges common perceptions, which often focus on simpler methods like scratching dates on bones. The Nebra Sky Disc represents a non-linear path to modern astronomy, with starts and stops, and a reliance on material objects rather than written records.

Further evidence of ancient astronomical understanding comes from gold hats found in similar regions. These hats depict solar circles, moon symbols, and numerical patterns of dots representing the number of moon phases within an 18-year solar cycle—an impressive calculation, though some numerical adjustments are needed for perfect accuracy.

Another major shift that potentially reflects astronomical information is the change in burial practices. After the Únětice people, the tumulus people began constructing massive stone and earthworks, known as megalithic burials, such as Newgrange in Ireland. This shift from smaller, family-based burials to large, solar-aligned structures suggests a change in worship, possibly from an earth-worshipping culture to a sun-worshipping one, potentially coinciding with major volcanic activity. However, sufficient academic sources to definitively link this shift to volcanic activity are currently lacking.

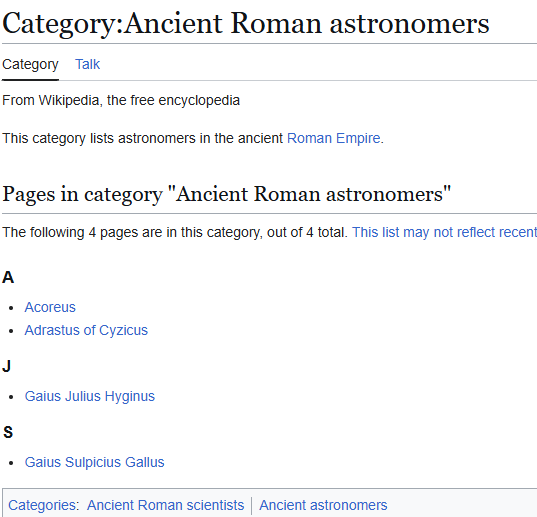

The next major historical development in this region was the incursion of the Eastern world into Central and Western Europe, brought by Roman soldiers. It's somewhat amusing that a quick search for famous Roman astronomers yields only four names on a prominent encyclopedia, while Greek astronomers number ten times that. Though not comprehensive, this stark difference is notable.

The astronomy of the Roman Empire often appears utilitarian their instruments seem closely related to the surveying equipment of the time, a stark contrast to the whimsical and speculative interpretations of the ancient Greeks. This dichotomy is understandable, given that the Romans inherited the definitive Ptolemaic and Aristotelian texts, notably the Almagest.

I often inquire if an audience is familiar with the Almagest. For those who are, please excuse my simplified explanation. For others, the Almagest literally means "the greatest" and was considered the final word in astronomy for a long time. Any subsequent astronomical work was seen as merely a refinement. It was believed to have covered everything, with only minor data table adjustments being permissible. This acceptance, particularly in later European history, was partly due to the Church's endorsement of its cosmology (with minor alterations). However, it was also an appeal to authority; to contradict Aristotle and Ptolemy, authors of "The Greatest," was to claim superiority.

Aristotelian cosmology, a refinement of Ptolemy's, presented a hierarchical universe, a concept that appealed to the hierarchical Church. The innermost spheres make intuitive sense: if you mix water, dirt, and air in a container, they quickly separate. Dirt sinks, water floats above it, and air above that. Similarly, if you mix air, fire, and water, water condenses and falls, air settles in between, and hotter air rises. This leads to a cosmology of Earth, water, air, and fire, with a fifth element, quintessence, beyond that.

Quintessence, lighter than fire, makes up the celestial spheres, which move around the Earth. Closer objects, like the Moon, move faster (completing a circuit in 29.5 days). Beyond the Moon are Mercury (the fastest wandering planet), then Venus, the Sun, Mars, Jupiter, and finally, the slowest wandering planet, Saturn. Beyond Saturn are the unmoving stars.

This model was somewhat understandable, passing the "back of the napkin" test. It also had Church endorsement and was somewhat predictive. However, after a considerable period, and with increasing sophistication, astronomers noticed that calculations based on this model for planetary positions eventually became inaccurate. Even with the most precise adherence to Ptolemy's prescribed motions, the results were never exact. It was assumed that while Ptolemy had codified astronomical knowledge, his calculations might be imperfect, offering an avenue for improvement through better data tables. This marked the earliest stirrings of modern astronomy: the idea that ancient knowledge could be refined and improved with more precise, accurate, and scientific methods.

This shift began much earlier than often imagined, with hints appearing in the "light ages" a thousand years ago. Planetary calculators, for instance, were developed around 1300. This era brought fascinating revelations. For me, one was realizing that while I envisioned the iconic astrolabe as a massive, precisely crafted metal instrument, depictions in art often show them made of wood or paper. These everyday tools simply haven't survived, which is both amazing and disappointing.

These refinements and the spirit of testing Ptolemy's and Aristotle's hypotheses gradually led us closer to modern astronomy, hundreds of years before its traditional dating. Ptolemy's ideas were slowly taken off their pedestal and made assailable. While not immediately toppled, their overthrow became a possibility as more observations contested his conclusions. This set the stage for new ideas, such as the Earth moving around the Sun. This idea was testable: if the Earth moved, we should observe a parallax in constellations—closer on one side of our orbit, farther on the other. The lack of observable parallax was explained by the stars' immense distances.

The true transition to modern astronomy, moving from its medieval, antiquity-rooted foundations to the science we know today, occurred with Copernicus, Galileo, and Kepler. This is a story I'm always excited to share. It's crucial to acknowledge that we stand on the shoulders of giants, but these giants don't solely originate in the 1700s; they, too, stood on the shoulders of earlier, more universal giants. This is a story of astronomy I feel connected to and am happy to pass on, but it's not the only story. There are parallel narratives, earlier and later. This was just the one I wanted to tell today. I'm happy to answer any questions about this story, and for others, I might be able to direct you to resources.

Thank you for joining me. Here's to clear skies, dark skies, and bright futures.

Image Credits

Carved bones:

Ivankovic, Milorad. (2020). Vedic Dialectics. 1. 1-51. By Joeykentin - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=137144641

Pommelte images:

Dirk Wandel: Inside the circles

Nebra Sky Disc:

The Nebra Sky Disc. © State Office for Heritage Management and Archaeology Saxony-Anhalt, Juraj Lipták.

Gold Hats:

By Photograph by Mike Peel (www.mikepeel.net)., CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=58210955By Kmtextor - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=48712766

Ptolemy's almagest cosmology

Cambridge concise History of Astronomy, Hoskins, M, Ch 1. Fig 1. Pg 3

Wikimedia commons

Citations

Ruggles, C. L. N., & Martlew, R. D. (1992). The North Mull Project (3): Prominent Hill Summits and Their Astronomical Potential. Journal for the History of Astronomy, 23(17), S1-S13. https://doi.org/10.1177/002182869202301702 (Original work published 1992)

Penprase, B. E. (2010). The Power of Stars: How Celestial Observations Have Shaped Civilization. Springer.

Hamacher, D., & Anderson, G. M. (2022). The first astronomers: How Indigenous Elders Read the Stars.

Aurignacian Lunar Calendar / diagram, drawing after Marshack, A. 1970; Notation dans les Gravures du Paléolithique Supérieur, Bordeaux, Delmas /

Hoskin, M. (1999). The Cambridge Concise History of Astronomy. Cambridge University Press.

“The Oldest Lunar Calendars, Soderman, NASA Staff, (https://sservi.nasa.gov/articles/oldest-lunar-calendars/)

Comments